April 15, 2018. This is the final installment of the blog post series “Reflections on how Europe handles emerging adults in trouble with the law” by Vincent Schiraldi, covering the innovative ways three European countries – Croatia, the Netherlands and Germany – respond to offending by emerging adults. Vincent Schiraldi, and his colleague Lael Chester, visited officials, facilities and programs in the Netherlands and Croatia before meeting a delegation of Massachusetts officials for the final leg of their tour in Germany.

Germany is the “grandfather” of special treatment for emerging adults amongst the three nations we visited, probably in all of Europe. The Germans have been trying young people up to age 21 in their juvenile justice system since 1953 and on the rare occasions they incarcerate them, doing so in juvenile facilities. Responding to the “fatherless generation” of young people following World War II, German leaders decided not to institutionalize youth in great numbers, but rather to rehabilitate and shield them from some of the harsher aspects of its adult system (still a relatively mild system by comparison to the U.S. both in terms of the numbers of people incarcerated and prison conditions).

The Massachusetts Delegation

When we completed our three-country tour, we did so with a delegation of over 20 representatives from the Massachusetts legislature, judiciary, prosecution, defense, law enforcement, executive branch, youth corrections, advocacy and treatment community. Interestingly, they are busy positioning the Commonwealth to become the “grandmother” of emerging adult reforms in the U.S. (although they’re vying with several other jurisdictions in doing so).

This was as smart, hard-working and decent a group of officials as one could ask for. They were and are involved in innovating with this population of young people in myriad ways. Since 2015, after the Harvard Kennedy School Program in Criminal Justice issued a reportthat I co-authored with Bruce Western examining the U.S.’s response to emerging adults, Roca’s Molly Baldwin and I have been convening key stakeholders to foment innovation in this space, many of whom came on the Germany trip. MassINC issued a report on emerging adults and held a forum I spoke at along with Sen. Will Brownsberger, who co-chairs the Judiciary Joint Committee.

Senator Brownsberger joined us in Germany; check out his excellent blog post about Germany’s approach. The Senator and I have had ongoing conversations about this population each time we’ve run into one another since the MassINC event.

A host of potential reforms have flowed from this vibrant set of conversations: (1) the courts have announced their intention to create specialized courts for emerging adults, (2) several Sheriffs, including Suffolk County Sheriff Steve Tompkins, have announced the opening of specialized living units for emerging adults, (3); and the Coalition for Juvenile Justice has a campaign geared at raising the age of juvenile court to 21. Meanwhile, the Department of Juvenile Justice already allows youth who “age out” to voluntarily continue receiving services beyond the expiration of their terms and programs like Roca and UTEC exclusively service an emerging adult population.

This year, the Massachusetts Legislature (five of whose members joined the Germany tour) grappled with several bills to raise the age of juvenile court to either 19 or 21. Literally the day before leaving for Germany, a conference committee of the Massachusetts House and Senate announced a 100-page criminal justice bill. While raising the upper age of juvenile court past 18 did not come out of committee (although it had passed the Senate), the committee’s provisions affecting emerging adults included allowing youth up to age 21 to expunge their felony and misdemeanor records if they remained crime-free for 7 or 3 years, respectively. The committee also formed a task force to study and make recommendations specific to emerging adults – a group that is not as developmentally mature as older adults and with whom a recent report found the Massachusetts criminal justice system has its worst outcomes (for more about that bill, check out this Boston Globe editorial which ran while we were in Germany).

To say that this group was focused on this issue is a gross understatement.

The German system

Back to Germany…

Initially, after German law was changed in 1953 to allow youth up to age 21 when they committed their offense to be tried as juveniles, the percent of youth ages 18, 19 and 20 retained in juvenile court looked a lot like the Netherlands and Croatia – around 20% - while the rest were tried and sentenced as adults. But steadily over the years as German judges and prosecutors gained more faith in this approach, they used the juvenile system more and more frequently for their emerging adults who had committed more serious offenses. By the time we visited, 66% of emerging adults who ran afoul of the law were tried as juveniles as were over 90% of those who had committed homicide and rape (the highest rate of trying these young people as adults was amongst traffic offenses). Youth can receive sentences of up to 10 years under juvenile law, but rarely do, fewer than 1% receive sentences of five to 10 years, fewer than 5% receive sentences of between three and five years.

Youth under age 14 are not criminally responsible and prior to age 18, youth cannot be tried under adult law. This essentially pushes the entire system upward to be more of an older juvenile/young adult system. For example, in one of the youth prisons we visited around 19 out of every 20 incarcerated youth was older than 18. This higher minimum age is not unusual in Europe – 12 is the international standard and is the Dutch age of responsibility, while in Croatia, the minimum age is 14 like Germany. Interestingly, the Massachusetts minimum age will rise to 12 if the legislation outlined above passes, making it the highest minimum juvenile court age in the U.S.

The German system prioritizes diversion and minimized intervention, mediation and restorative practices, and educational community sanctions. Community service and direct payments can be geared, for example, to repaying victims through labor. Deprivation of liberty is a last resort.

In a hearing the delegation witnessed, a young adult with several prior involvements with the law fired a realistic-looking starter pistol while drunk in the Berlin subway system on New Year’s Eve a little more than a year ago. The courts attempted mediation with the victim – a woman who was nearby when he fired the shot which halted her train – but she had moved her residence and was unavailable. She attended the hearing, a combination of trial and sentencing during which the youth had no representation, and was offered, but turned down, a 100 Euro compensation for pain and suffering. By all appearances, she harbored no ill will towards the youth being tried. The youth was convicted and fined 200 Euro.

The mission of the German system is clear. Children (under 14 years), juveniles (14-17) and young adults (18-20) have the right to support and education and to be protected in their personal development by the child and youth welfare agencies. Youth services are established at the local community level, where priority is given to private non-profit organizations which must be accredited by the state level youth welfare departments of the ministries of social affairs – analogous to our state child welfare agencies.

This educational and rehabilitative ethic also holds true when youth are incarcerated. According to Germany’s Youth Courts Law, when a youth is confined, it should “arouse the youth’s sense of self respect,” “be structured in an educational manner” and “help the youth to overcome those difficulties which contributed to his commission of the criminal offense.”

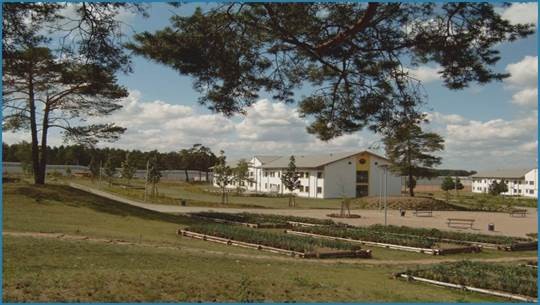

The Neustrelitz Youth Prison

The rehabilitative ethic of Germany’s youth system was on full display when we toured the Neustrelitz Youth Prison. Neustrelitz was in the rural, northeastern state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. Staff there and throughout the German system are required to undergo two years of training prior to working as correctional officers.

As noted above, the population of the facility was the equivalent of a U.S. prison incarcerating young adults, rather than a juvenile facility, even though the youth in it were all incarcerated pursuant to juvenile law. Ninety-six percent of the youth were older than 18 and since it’s not easy for a youth to get a prison term in Germany, the youth tended to be incarcerated for more violent offenses than U.S. juvenile facilities (care needs to be taken in cross-national comparisons; violence, particularly gun violence, is far less prevalent in Germany than in the U.S.).

The staff were highly professional and treatment of the young people was highly normalized, particularly when compared to U.S. adult prisons. The level of vocational programming was astonishing, with professional woodworking, metal working, culinary and farm working (including award-winning rabbit husbandry) dominating the youths’ daily programming.

The level of freedom offered the youth was extraordinary by U.S. standards. For example, youth served us a tasty meal shortly after arrival with real knives and forks; sharp equipment in the vocational shops was everywhere; and nowhere was there the sense of fear and heavy correctional hardware (pepper spray, solitary confinement) that dominates the U.S. correctional landscape.

Clearly, not only were the Germans incarcerating fewer of their young adults, but they were incarcerating them in better conditions than our adult systems.

What was remarkable to me was how much these predominantly young adult facilities resembled well-run juvenile systems in the U.S. The Massachusetts system, for example, has a long history of running decent and rehabilitative facilities, reserving secure care for youth with the most serious offenses and a continuum of community programs for those with less serious offenses/prior records. Peter Forbes, Commissioner of Massachusetts Department of Youth Services (DYS) was part of the delegation and informed us that Massachusetts had about 100 youth in secure custody (in a state of 6.9 million).

Having toured both the Massachusetts system and Neustrelitz, the culture and rehabilitative ethic were strong in both. I have little problem imagining DYS being able to work with emerging adults in Massachusetts either in the community programming or secure care, especially if they were able to beef up their vocational programming.

A final thought on possibilities

Emerging adults are more immature than their older counterparts – they’re greater risk-takers, less future oriented, and are more volatile in emotionally charged settings, especially around their peers. The adult roles that help young people, particularly young males, mature out of criminality – marriage and steady work – are available much later than they were for previous generations, certainly much later than they were for my generation in the late 1970s.

About one out of every five people entering U.S. prisons are young adults. They have the worst outcomes. Racial disparities in prison roles for them exceed even the outrageous disparities that plague U.S. incarceration overall.

This is a population that needs special attention.

The Council of Europe recommends:

Reflecting the extended transition to adulthood, it should be possible for young adults under the age of 21 to be treated in a way comparable to juveniles and to be subject to the same interventions.

Several jurisdictions, including and perhaps especially Massachusetts, are looking into special treatment for emerging adults when they break the law, ranging from raising the juvenile court age, to special facilities, courts and caseloads, to special programming.

Clearly, there are substantial cultural differences between the U.S. and Europe, just as there are substantial differences between U.S. states. No one expects to go to Croatia, Germany and the Netherlands and borrow their systems wholesale, any more than people expect the systems in Massachusetts and Wisconsin to be the same. But that doesn’t mean that such delegations can teach officials and academics nothing on both sides of the pond.

When we debriefed at the end of our journey and participants were asked to give their thoughts on what we had witnessed, one respondent said simply, “possibilities.” By this, he explained that he meant that while no system could be adopted whole cloth, the tour had opened his eyes to possibilities that we need to explore for this population, a population that is both challenging and full of opportunities.

I hope this series has opened up similar possibilities to those who have read through it.

A version of this blog piece, In Germany, It’s Hard to Find a Young Adult in Prison, was published on The Crime Report, on April 10, 2018.